Clarity

Authors

- Kevin Moran, George Mason University

- Ali Yachnes, William & Mary

- George Purnell, William & Mary

- Junayed Mahmud, George Mason University

- Michele Tufano, Microsoft

- Carlos Bernal Cardenas, Microsoft

- Denys Poshyvanyk, William & Mary

- Zach H’Doubler, William & Mary

Introduction

Graphical User Interface (GUI) based applications predominate user-facing software in the modern era of computing. High quality applications with well-designed GUIs allow users to instinctively understand underlying features. Thus, intuitively, certain functional properties of applications are encoded into the visual, pixel-based representation of the GUI such that cognitive human processes can determine the computing tasks provided by the interface. This suggests that there are certain latent patterns that exist within visual GUI data which indicate the presence of natural use cases capturing core program functionality. This functionality can be easily interpreted and communicated in natural language (NL) by users after simply glancing at a GUI.

Given the inherent representational power of GUIs in conveying program related information, we set forth the following hypothesis that serves as the basis for the work undertaken in this project:

We are interested in understanding the potential of rich GUI-based representations to support tasks related to automated documentation; a key area of research related to several open problems that sit at the intersection of software documentation, design, and testing. We are interested in exploring the above hypothesis due to the potential impact that advancements in GUI-centric program comprehension could have on important SE tasks.

To investigate the potential of automated GUI-centric software documentation, we offer one of the first comprehensive empirical investigations into this new research direction's most fundamental task: generating a natural language description given a screenshot (or screen-related information). To accomplish this, we collect and analyze what is, to the best of the authors' knowledge, the largest dataset of functional descriptions of software GUIs. Furthermore, to investigate the representational power of GUIs to encode information related to functional properties of software, we train and test four Deep Learning (DL) approaches for image captioning, three that learn from image data and one that learns from textual GUI metadata, to predict functional descriptions of software at different granularities. We evaluate the efficacy of these models both quantitatively, by measuring the well accepted BLEU score metric, and qualitatively through a large-scale user study.

Background

The Connection between Images and NL

A longstanding research challenge in the field of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) has been to enable computational programs that are capable of intelligently understanding visual information. Granting computers this ability to comprehend and communicate about images in NL could lead to highly impactful applications, from advancements in intelligent virtual assistants to automated medical diagnoses. In recent years DL-based approaches have proven particularly transformative for several image comprehension tasks. These DL-based techniques have evolved to tackle increasingly more difficult problems. Research has progressed from image classification using large scale datasets like ImageNet, to more advanced tasks including image captioning and dense image captioning. In image classification tasks, a model is trained to evaluate a given image and assign it one of a set of predefined categories. DL-based approaches for this task have surpassed human levels of accuracy. Conversely, image captioning, wherein a model is trained to predict an appropriate sentence to describe an image, are generally still under active research.

The task of image captioning is much more difficult than that of classification, as an effective model must be able to both learn salient features from images automatically and semantically equate these features with the proper NL words and grammar that describe them. This task of semantically aligning two completely different modalities of information has led to the development of multimodal DL architectures that jointly embed NL and pixel-based information in order to predict an appropriate description of a given input image. These techniques are typically trained on large-scale datasets that contain images annotated with multiple captions, such as MSCOCO, and have largely drawn inspiration from encoder-decoder neural language models traditionally applied to machine translation tasks. In this paper, we explore three recent architectures for image captioning applied to captioning software screenshots with functional descriptions, neuraltalk2, Google's im2txt framework and show, attend and tell framework, in addition to one neural language model, Google's seq2seq model. We briefly describe these architectures below, starting with the seq2seq model.

Google's Neural Machine Translation Model (seq2seq): Several studies have illustrated the successes of encoder-decoder Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) for the task of machine translation. The general task defined by machine translation is to transform an input sentence written in one language, to a target translation in another language. Encoder-decoder RNNs typically function by having an ''encoder'' RNN parse a sentence and transform it into a vector-based embedding space. Then, this embedding space is used as input to a ''decoder'' RNN that aims to generate the target sentence. These models are trained on large NL corpora containing both source and target sentences, and the network weights are trained to minimize prediction error. Google's seq2seq framework is a generalized architecture for neural machine translation tasks, and in this paper, we investigate its potential to translate from lexical GUI metadata to NL descriptions of software.

Google's Neural Image Captioning Architecture (im2txt): Google's DL model for image captioning builds upon the success of encoder-decoder neural language models. The im2txt framework treats image captioning as a machine translation problem, wherein the source ''sentence'' is an image, and the target ''translation'' is a NL sentence. The generalized architecture of im2txt is shown in Fig. 1. As illustrated, im2txt replaces the encoder RNN with a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), which have been shown to be highly capable of learning rich image features. Google's implementation uses a Long-Short Term Memory (LSTM) RNN for the ''decoder'' module, which has also proven extremely effective when applied to machine translation tasks. LSTM RNN units are capable of ''remembering'' data values over an arbitrary time period via three gates that regulate information flow. In this architecture, the CNN weights are pre-trained on a large image classification dataset (e.g. ImageNet).

Karpathy et.al.’s NeuralTalk2 Architecture: The NeuralTalk2 model architecture proposed by Karpathy et.al. functions along the same general principles as im2txt, with certain key differences. neuraltalk2 shares the goal of predicting a sentence given an input image, and does so with an architecture that jointly embeds both image data and NL sentence data in a shared semantic embedding space. However, unlike im2txt, NeuralTalk2 uses a Region CNN (RCNN) that is capable of detecting and labeling multiple objects within a single image by combining a CNN with a region proposal algorithm. Furthermore, the "decoder'' component used by Karpathy's architecture is composed of a Bidirectional RNN (BRNN) as opposed to an LSTM. BRNNs function similarly to a standard RNN, however the derived word embeddings are richer data representations thanks to the inclusion of sentence context around a given word (i.e. including context from other words surrounding a given word). Neuraltalk2 is trained in a similar manner to im2txt, where the CNN weights are pre-initialized on a large image classification dataset, and the RCNN is trained end-to-end using the CNN embeddings to predict sentences.

Show, attend and Tell: The show, attend and tell model describes the content of an image using attention. This model generates captions using the attention that combines "hard" and "soft" attention mechanisms. The first one uses standard back-propagation methods, and the second uses a maximum approximate variational lower bound for training. The model uses a CNN as an encoder to extract a set of feature vectors and use it as input for the attention mechanism. The model uses an LSTM as a decoder to generate caption. LSTM is also one kind of RNN capable of learning long-term dependencies, whereas standard RNN has a short-term memory, which does not work well when a caption contains long texts. Therefore, we might miss essential facts for screenshots. LSTM is a good choice in that situation. We get the final predicted captions based on the hidden state of the LSTM, context vector, and the words that we get from the encoding phase.

Mobile Graphical User Interfaces

GUIs of Android apps are composed of both GUI-components and GUI-containers, which together form a GUI-hierarchy. GUI-components represent atomic widgets that carry with them a pre-defined base functionality (e.g. Button, Spinner, NumberPicker). GUI-containers organize GUI-components into logical groups, and define certain spatial or stylistic properties of the contained GUI-components (e.g., grouping together TextViews on a panel with a certain color background). A hierarchal nesting of GUI-components and GUI-containers forms a rooted tree structure, where a single GUI-container serves as the root of the tree. In Android, this GUI-structure is stipulated in static code by xml files in the resource directory of an Android app (e.g. the /res/layout directory). This same GUI-structure is represented dynamically at runtime by metadata defined by an xml structure which can be read from an Android device using Android's uiautomator framework. Fig. 2 illustrates the runtime xml representation of a Ringtone app. The three highlighted xml snippets represent the corresponding GUI-metdata for the Menu button, as well as the "New'' card, and the "Abstract'' card, which allow users to browse various categories of ringtones. In many ways, the GUI-metadata described above constitutes another representation for software GUIs, one that is lexical in nature. Furthermore, it is possible that the information encoded into GUI-metadata is complimentary to what is encoded by pixel-based screenshots. However, it is clear that not all attributes included in GUI-metadata would be useful as a rich representation (i.e., many attribute fields are often just "false''). Thus, to perform a thorough investigation of the latent potential for different GUI representations to encode functional properties, we explore whether the seq2seq model can effectively translate between differing collections of GUI-metadata attributes and NL descriptions.

The CLARITY Dataset

Collecting the Clarity Dataset

To collect the Clarity dataset, we utilized the ReDraw dataset of screens and GUI-component information with additional filtering techniques applied to remove landscape screens, blank screens, and screens with semi-transparent overlays. This process resulted in a candidate set of 17,203 screens suitable for the labeling process.

Once we derived a suitable set of screens, we needed to manually label these screens with functional captions. After an initial pilot study to confirm the validity of our labeling process we performed a full scale data collection study using Amazon's Mechanical Turk Crowd-worker platform to collect over 10k screens with functional descriptions.

Caption Granularity: Intuitively, GUIs encode functional information at multiple levels of granularity. For example, if you were to ask a user or developer what the high-level purpose of a given screen is, they might say, "This screen allows users to browse clothing categories'', as shown in Fig. 3. These types of descriptions constitute the “high-level” functionality of a given screen. However, a single screen rarely implements only one functionality, and there may be multiple functional properties that enable the screen's high-level functional purpose. User descriptions of these types of functional properties are typically centered around the interactive components of a screen, since these represent the instances of actions (e.g., users “doing something”) that are easily attributed to implemented functions. For example, in the screen in Fig. 3, underlying functions include viewing favorites, accessing a shopping cart, or selecting an item from a list. These types of "low-level'' screen properties centered around GUI-components describe key constituent functionality. Hence, in order to capture a holistic functional view of each screen, we tasked participants with labeling each screen with one “high-level” functional caption, and up to four "low-level'' functional captions. Fig. 3 shows these two categories using actual captions collected as part of the Clarity dataset.

Mechanical Turk Data Collection Study: After the initial pilot study and additional round of screen inspection and filtering, we collected functional image captions at large scale using MTurk. To set up this data-collection process, we configured a Human Intelligence Task (HIT) that provided workers with a set of detailed instructions, displaying a screenshot from our dataset alongside text entry boxes for one high-level functional caption and up to four low-level functional captions. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the authors' affiliated institution.

MTurk provides various levels of configuration for a given HIT to help target certain populations of users for specific tasks based on demographic information and their qualifications as a crowd worker (e.g., their number of successfully completed HITs). Additionally, you can set the price paid to each worker for satisfactorily completing a given HIT. When a worker completes a HIT, it must be "accepted'' by the requester before the participant is paid, allowing for control over the quality of submissions from workers. Given that we aimed to collect high-quality functional descriptions of screens in natural English, we targeted MTurk users from primarily English speaking countries that had completed at least 1,000 HITs and had a HIT approval rate of at least 90%. We provided a detailed set of instructions for labeling images with captions that clearly explained the concept of high-level and low-level captions with examples, and provided users with explicit instructions as well as DOs and DONTs for the labeling task. The full set of instructions can be viewed by clicking the button above. With regard to caption quality, we specifically had three major requirements: (i) that the caption describes the perceived functionality of a screen and not simply its appearance, (ii) that spatial references are given for low-level captions (e.g., “the button in the top-left corner of the screen”), and (iii) that captions be written in complete English sentences with reasonably proper grammar. We opted to require screen location information for low-level components to investigate whether such spatial relationships could be learned from visual GUI-related data.

We published batches of HIT tasks by sampling unique screens from our set of candidate screens, ensuring that no user was assigned the same screen twice. The quality of work from crowd-sourced tasks is not always optimal, so as captions were submitted, they needed to be vetted for quality. To perform quality vetting, we implemented a Java app that displayed screenshots with their corresponding crowdsourced captions, as well as options for rejecting/accepting these captions. Using this tool, The captions for each screen were examined by at least one author for the three quality attributes mentioned above. If an author was unsure about whether a screen met these quality attributes, it was reviewed by at least one other author to reach a consensus. In summary, we collected a total of 45,998 captions (across granularity levels) for 10,204 screens, and paid out over $2,400 to workers.

Clarity Dataset Analysis

The Clarity dataset provides a rich source of data for exploring the relationship between GUI-based and lexical software data. However, it is important to investigate the semantic makeup of the collected captions in order to better understand: (i) the latent topics they capture as well as (ii) their naturalness and, hence, predictability. This type of investigation should lead to insights regarding the ability of such NL descriptions to be appropriately modeled and thus predicted to facilitate program comprehension. In this section we carry out an empirical analysis of this phenomena guided by the following two Research Questions (RQs):

Results of Clarity Dataset Topic Modeling (RQ1)

| Assigned Label | Top Seven Words |

|---|---|

| Sign Up Page | applic screen display sign page use show |

| App Terms | screen user provid app inform allow term |

| Color Options | screen show app option color book differ |

| Video Game Home | screen page show app video game home |

| Login or Create Account | user screen allow account log creat app |

| Enter Email and Password | user screen enter password email allow address |

| Choose App Language | user screen allow choos access app languag |

| Select Image from List | user screen allow select view list imag |

| Map Search by Location | screen locat search map user show find |

| Facebook Login Screen | page screen app show login websit facebook |

| Assigned Label | Top Seven Words |

|---|---|

| app logo | screen app text center bottom indic logo |

| page button | page button top center bottom side left |

| game start | user click button game bottom view start |

| select date | avail date select one option theme present |

| wallpaper options | set screen show option wallpap ad chang |

| top left back button | button user screen left top corner back |

| camera button | video imag photo pictur screen bottom camera |

| popup cancel button | button popup cancel bottom screen right box |

| name field | first second row third last name question |

| privacy policy banner | titl just term blue banner privaci polici |

We present selected results of some of the most representative topics in Tables 6 & 7, complete with descriptive labels that we provide for readability, whereas all results can be downloaded by clicking the button above. These topics help to provide a descriptive illustration of some of the latent patterns that exist in both the high and low level Clarity captions. The high-level captions illustrate several screen level topics, including searching on a map and adjusting app settings. The low-level captions conversely capture topics that describe component-level functionality, such as date selectors, camera buttons, and back buttons. These results indicate the existence of logical topics specific to the domain of GUIs in our collected captions.

Results of n-gram Language Modeling on the CLARITY Dataset (RQ2)

The results of our naturalness analysis are illustrated in Figure 4. This figure shows the average cross entropy of the high- and low- level captions from the Clarity dataset compared to several other corpora as calculated by Rahman. More specifically, the graph depicts the average ten-fold cross entropy for: (i) The Gutenberg corpus containing over 3k English books written by over a hundred different authors, (ii) Java code from over 134 open source projects on GitHub, (iii) Java without Syntax Tokens (i.e., separators, keywords, and operators), and (iv) a Stack Overflow corpus consisting of only the English descriptions from over 200k posts.

As described earlier, the lower the cross-entropy is for a particular dataset, the more natural it is. That is, the corpora that exhibit lower cross entropy tend to exhibit stronger latent patterns that can be effectively modeled and predicted. As we see from Fig. 4, the Clarity high and low level captions are more natural than every dataset excluding raw Java code. This signals that our collected captions exhibit strong semantic patterns that can be effectively modeled for prediction. Additionally, we observe that the cross-entropy for the high and low-level captions are surprisingly similar. Intuitively, one might expect that the low-level Clarity captions would exhibit more prevalent patterns due to the repetitive use cases of certain GUI-components such as menu buttons. However, we see only minor differences between the two corpora. This indicates the proclivity of both datasets to exhibit patterns that can be appropriately modeled.

Empirical Study

We aim to learn whether state-of-the-art DL models can appropriately predict a natural language description of functionality given both pixel-based and metadata-based GUI information. Thus, we perform a comprehensive empirical evaluation with two main goals: (i) intrinsically evaluate the predictive power of the models according to well accepted machine translation effectiveness metrics, and (ii) extrinsically evaluate the models by examining and rating the quality of the predicated functional NL descriptions. The quality focus of this evaluation is our studied models' ability to effectively predict accurate, concise, and complete functional descriptions. To aid in achieving the goals of our study, we define the following RQs:

Image Captioning Model Configurations

| Model | Identifier | Caption Config. | Model Config. |

|---|---|---|---|

| im2txt | im2txt-h-imgnet | High | inception v3 trained on imagenet |

| im2txt-l-imgnet | Low | ||

| im2txt-c-imgnet | Combined | ||

| im2txt-h-comp | High | Inception v3 fine-tuned on Component Dataset | |

| im2txt-l-comp | Low | ||

| im2txt-c-comp | Combined | ||

| im2txt-h-fs | High | Inception v3 fine-tuned on Full Screen Dataset | |

| im2txt-l-fs | Low | ||

| im2txt-c-fs | Combined | ||

| NeuralTalk2 | ntk2-h-imgnet | High | VGGNet pre-trained on ImageNet |

| ntk2-l-imgnet | Low | ||

| ntk2-c-imgnet | Combined | ||

| ntk2-h-ft | High | VGGNet pre-trained on ImageNet with Fine Tuning | |

| ntk2-l-ft | Low | ||

| ntk2-c-ft | Combined | ||

| Show, Attend & Tell | sat-h | High | VGGNet pre-trained on ImageNet |

| sat-l | Low | ||

| sat-c | Combined |

We train and test the three state-of-the-art image captioning models, im2txt, neuraltalk2, and show, attend and tell (SAT), on the screenshots and captions of the Clarity dataset. We choose to explore these three models due to their different underlying design decisions related to the type of utilized CNNs and RNNs (See background above), as these differences may affect their performance in our domain. These models contain several different configuration options that provide a rich experimental space of their effectiveness. However, given the typical number of parameters that constitute these models, the training time can be quite prohibitive, even on modern hardware. Thus, to control our experimental complexity and investigate a number of model configurations that can be trained in a reasonable amount of time, we fix the values of the hyper-parameters for each model in our experiments. We derived our utilized hyper-parameter values by conducting brief random searches for optimal values of certain parameters, and chose optimal parameters reported in prior work for others. While we fix the hyper-parameters for these models, we instead vary the configurations of our image captioning models at the architecture level. Specifically, we investigate how training the ''encoder'' CNN using different datasets and training procedures affects the efficacy of the model predictions. This type of analysis allows us to more effectively flush out broader patterns related to the benefits and drawbacks of fundamental model design decisions. In the end, we trained more than 15 different configurations of the image captioning models (See Table 1), not including initial parameter searches, over several machine months of computation.

| Hyperparameter | Value Used | Hyperparameter | Value Used |

|---|---|---|---|

| values_per_input_shard | 2300 | lstm_dropout_keep_prob | 0.7 |

| input_queue_capacity_factor | 2 | num_examples_per_epoch | 58000 |

| num_input_reader_threads | 8 | optimizer | SGD |

| self.vocab_size | 12000 | initial_learning_rate | 2 |

| .num_preprocess_threads | 8 | learning_rate_decay_factor | 0.5 |

| batch_size | 64 | num_epochs_per_decay | 8 |

| initializer_scale | 0.08 | train_inception_learning_rate | 0.005 |

| embedding_size | 512 | clip_gradients | 5 |

| num_lstm_units | 512 | max_checkpoints_to_keep | 5 |

im2txt Model Configurations & Training: For im2txt, we utilized Google's open source implementation of the model in TensorFlow. Given the incredibly large number of parameters that need to be trained for the im2txt model, performing even relatively simple hyperparamter searches proved to be computationally prohibitive for our experiments. Therefore, for this model we utilized the optimal set of parameters reported by Vinyals et.al. on similarly sized datasets. The hyper parameters utilized for our models are given Table 2. The publicly available implementation of Google's im2txt model utilizes the Inception v3 image captioning architecture as its encoder CNN. In past work, the inception model weights were initialized by training on the large-scale image classification dataset imagenet, which contains thousands of categories representing “commonplace” subject categories (e.g. tree, cat, dog, etc). However, given that we are applying these models to very particular domain (predicting descriptions of software) it is unclear if an Inception v3 model trained on the broader imagenet dataset would capture subtle semantic patterns in the Clarity dataset. Therefore, we explored three different model configurations to explore this phenomena: one with Inception v3 pre-trained on imagenet, and two with Inception v3 fine-tuned on domain specific-datasets. The first domain specific image dataset we utilize is the ReDraw cropped image dataset, which contains over 190k images of native Android GUI-components labeled with their type (e.g., Button, TextView). The second domain specific image dataset we use consists of the full screenshots from the Clarity dataset, labeled with their Google Play categories. For the ReDraw cropped image dataset, we utilize the train/val/test split provided by the authors, whereas for the full screenshot dataset, we perform an even 80/10/10 split across labeled categories.

The Inception v3 models utilizing our domain specific cropped and full image datasets were trained for 1 million iterations, and achieved 94% and 98% top-1 precisions respectively. The im2txt models were trained on the shared Clarity training set for the high, low, and combined caption configurations for 500k iterations, with checkpoints being saved every 2,000 iterations. Given the prohibitive training time, we did not perform joint-fine tuning of the weights of the CNN and RNN for im2txt. Instead, we explore the effects of joint-fine tuning with the NeuralTalk2 models.

| Hyperparameter | Value Used | Hyperparameter | Value Used |

|---|---|---|---|

| rnn_size | 512 | optim_beta | N/A for sgd |

| input_encoding_size | 512 | optim_epsilon | 1.00E-08 |

| batch_size | 16 | cnn_learning_rate | 1.00E-05 |

| grad_clip | 0.1 | cnn_weight_decay | 0 |

| drop_prob_lm | 0.7 | cnn_optim | sgd |

| max_iters | 500 000 | cnn_optim_alpha | 0.8 |

| learning_rate | 2 | cnn_optim_beta | 0.999 |

| learning_rate_decay_start | 10 000 | cnn_learning_rate | 9.99E-01 |

| learning_rate_decay_every | 50 000 | finetune_cnn_after | 0 |

| optim | sgd | cnn_weight_decay | 0 |

| optim_alpha | N/A for sgd | seed | 123 |

NeuralTalk2 Model Configurations & Training: For neuraltalk2, we utilized Karpathy et.al’s implementation written in Torch and lua. We performed a brief randomized hyper-parameter search for this model, given its more efficient training time, using the optimal im2txt parameters as a starting point . The optimal values resulting from this search are provided in Table 3. For its CNN decoder, neuraltalk2 makes use of a VGGNet architecture pre-trained on the ImageNet dataset. Unlike our im2txt configurations, we explore the effect of jointly fine-tuning neuraltalk2's CNN and RNN. Thus, we explore two configurations of neuraltalk2, one that jointly fine tunes the pre-trained VGGNet on the Clarity dataset, and one that does not perform fine-tuning. We followed a training procedure similar to that of our im2txt models, in that we trained our models on the high, low, and combined Clarity caption training data for 500,000 iterations, saving model weight checkpoints every 2,000 iterations.

| Hyperparameter | Value Used | Hyperparameter | Value Used |

|---|---|---|---|

| dim_embedding | 512 | learning_rate_decay_factor | 1.0 |

| dim_decode_layer | 1024 | num_steps_per_decay | 100000 |

| fc_drop_rate | 0.5 | clip_gradients | 5.0 |

| lstm_drop_rate | 0.3 | momentum | 0.0 |

| attention_loss_factor | 0.01 | decay | 9.0 |

| batch_size | 17 | beta1 | 0.9 |

| Optimizer | Adam | beta2 | 0.999 |

| initial_learning_rate | 0.0001 | epsilon | 1e-6 |

| num_lstm_units | 512 |

Show, Attend and Tell Model Configurations & Training: For the SAT model, we adapted the open-source implementation of the model in Tensorflow. The hyperparameters that we used to train our model are shown in the Table 4 above. The implementation used VGG16 as its encoder CNN. We trained the SAT model on the CLARITY dataset for the low, high and combined captions for 500K iterations and kept the checkpoints after every 1K iterations. Note that due to the prohibitive training cost of this model, we did not explore using a fine-tuned VGGNet as we did with neuraltalk2.

Metadata Captioning Model Configurations

| Model | Identifier | Caption Config. | Model Config. |

|---|---|---|---|

| seq2seq | seq2seq-h-type | High | Trained on GUI Component Types |

| seq2seq-l-type | Low | ||

| seq2seq-c-type | Combined | ||

| seq2seq-h-text | High | Trained on GUI-Component Text | |

| seq2seq-l-text | Low | ||

| seq2seq-c-text | Combined | ||

| seq2seq-h-tt | High | Trained on GUI-Component Type + Text | |

| seq2seq-l-tt | Low | ||

| seq2seq-c-tt | Combined | ||

| seq2seq-h-ttl | High | Trained on GUI-component Type + Text + Location | |

| seq2seq-l-ttl | Low | ||

| seq2seq-c-ttl | Combined |

| General Hyperparameters | Value Used | Encoder parameters | Value Used |

|---|---|---|---|

| embedding.dim | 128 | cell_class | GRUCell |

| encoder.class | BidirectionalRNNEncoder | num_units | 128 |

| decoder.class | AttentionDecoder | dropout_input_keep_prob | 0.8 |

| optimizer.name | Adam | dropout_output_keep_prob | 1 |

| optimizer.learning_rate | 0.0001 | num_layers | 1 |

| source.max_seq_len | 50 | Decoder Parameters | Value Used |

| source.reverse | FALSE | cell_class | GRUCell |

| target.max_seq_len | 50 | num_units | 128 |

| Attention Parameters | Value Used | dropout_input_keep_prob | 0.8 |

| num_units | 128 | dropout_output_keep_prob | 1 |

| num_layers | 1 | ||

| Optimizer Parameters | |||

| epsilon | 0.0000008 |

To explore the ability to translate between the lexical representations of GUI-metadata and NL functional descriptions, we train and test an encoder-decoder neural language model using Google's seq2seq framework. We chose to utilize the default general-purpose architecture and hyper-parameters for this model, as they have been shown to be effective across a wide-range of machine translation tasks. More specifically, our encoder network consists of a BRNN composed of Gated Recurrent Units (GRUs) and our decoder network consists of an RNN composed of LSTM units. The hyper-parameters used in training this model are given in Table 6.

In contrast to the image captioning models, where the input to the encoder is an image, this model takes as input information from GUI metadata and predicts, or "translates" the corresponding NL caption. However, as illustrated in the Background, metadata-based representations of GUIs contain several attribute fields, not all of which may be helpful in learning latent semantic patterns. Therefore, to investigate the representative power of different attributes included in Android GUI-metadata, we create four configurations of GUI-metadata consisting of different attribute combinations (Table 5). We chose to utilize these attribute combinations as they represent (i) the attributes that are most likely to have values, and (ii) represent a wide range of information types (e.g., displayed text, component types, and spatial information). Each of these four sets is paired with the high, low, and combined sets of captions (Table 5), and segmented according to training, validation, and test sets consistent across all models. Consistent with the training procedures of the other models, our implementation of the seq2seq model was trained to 500k iterations, with checkpoints being saved every 2k iterations.

Empirical Results

Results from Quantitative Model Evaluation (RQ3)

The two tables below illustrate the BLEU score results for all model combinations trained (in the paper we only show the best performing model for readability’s sake). The best performing model configuration for each type of model are highlighted in blue.

| Model Name | Caption Configuration | Model Configuration | Composite BLEU Score | BLEU-1 | BLEU-2 | BLEU-3 | BLEU-4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| im2txt-c-imgnet | Combined | Inception v3 Pre-Trained on ImageNet | 0.302858 | 0.520607 | 0.360747 | 0.217637 | 0.112439 |

| im2txt-h-imgnet | High-Level | 0.123471 | 0.250284 | 0124310 | 0.066160 | 0.053129 | |

| im2txt-l-imgnet | Low-Level | 0.269517 | 0.457925 | 0.315951 | 0.199971 | 0.104220 | |

| im2txt-c-comp | Combined | Inception v3 Fine Tuned on ReDraw Cropped Images | 0.302978 | 0.516608 | 0.359123 | 0.220528 | 0.115653 |

| im2txt-h-comp | High-Level | 0.116127 | 0.242234 | 0.116822 | 0.057997 | 0.047454 | |

| im2txt-l-comp | Low-Level | 0.270481 | 0.456676 | 0.318999 | 0.200112 | 0.106137 | |

| im2txt-c-fs | Combined | Inception v3 Fine-Tuned on ReDraw Full Screenshots | 0.300721 | 0.513505 | 0.359870 | 0.216181 | 0.113326 |

| im2txt-h-fs | High-Level | 0.123994 | 0.248933 | 0.126139 | 0.067528 | 0.053376 | |

| im2txt-l-fs | Low-Level | 0.264500 | 0.449909 | 0.312707 | 0.188958 | 0.106428 | |

| ntk2-c-imgnet | Combined | VGGNet Pre-Trained on ImageNet No Joint Fine Tuning | 0.297983 | 0.524647 | 0.35956 | 0.210721 | 0.097001 |

| ntk2-h-imgnet | High-Level | 0.133537 | 0.273495 | 0.135113 | 0.072640 | 0.052902 | |

| ntk2-l-imgnet | Low-Level | 0.273620 | 0.470703 | 0.325110 | 0.200512 | 0.098157 | |

| ntk2-c-ft | Combined | VGGNet model pre-trained on ImageNet with Joint Fine Tuning | 0.301568 | 0.520519 | 0.360115 | 0.217828 | 0.107810 |

| ntk2-h-ft | High-Level | 0.126834 | 0.266716 | 0.125605 | 0.068949 | 0.046064 | |

| ntk2-l-ft | Low-Level | 0.273822 | 0.474743 | 0.328862 | 0.195099 | 0.096584 | |

| sat-c | Combined | VGGNet model pre-trained on ImageNet with Joint Fine Tuning | 0.377 | 0.568 | 0.420 | 0.305 | 0.220 |

| sat-h | High-Level | 0.177 | 0.301 | 0.183 | 0.129 | 0.098 | |

| sat-l | Low-Level | 0.350 | 0.525 | 0.387 | 0.281 | 0.207 |

| Model Name | Caption Type | Model Configuration | Composite BLEU Score | BLEU-1 | BLEU-2 | BLEU-3 | BLEU-4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| seq2seq-h-type | Combined | Trained on UI Component Types | 0.169 | 0.389 | 0.147 | 0.060 | 0.080 |

| seq2seq-l-type | High-Level | 0.174 | 0.407 | 0.140 | 0.085 | 0.065 | |

| seq2seq-c-type | Low-Level | 0.181 | 0.446 | 0.170 | 0.079 | 0.029 | |

| seq2seq-h-text | Combined | Trained on UI Component Text | 0.132 | 0.322 | 0.125 | 0.058 | 0.024 |

| seq2seq-l-text | High-Level | 0.141 | 0.401 | 0.0139 | 0.084 | 0.065 | |

| seq2seq-c-text | Low-Level | 0.156 | 0.369 | 0.152 | 0.075 | 0.030 | |

| seq2seq-h-tt | Combined | Trained on UI Component Type + Text | 0.119 | 0.303 | 0.108 | 0.049 | 0.019 |

| seq2seq-l-tt | High-Level | 0.162 | 0.374 | 0.134 | 0.080 | 0.060 | |

| seq2seq-c-tt | Low-Level | 0.133 | 0.323 | 0.132 | 0.057 | 0.020 | |

| seq2seq-h-ttl | Combined | Trained on UI Component Type + Text + Location | 0.116 | 0.291 | 0.113 | 0.044 | 0.017 |

| seq2seq-l-ttl | High-Level | 0.161 | 0.384 | 0.128 | 0.076 | 0.057 | |

| seq2seq-c-ttl | Low-Level | 0.136 | 0.325 | 0.136 | 0.061 | 0.024 |

Predicted Captions for Best Model Configurations

Below you can find all of the predicted captions for the im2txt, NueralTalk2, and Seq2Seq Models, as indicated by the results illustrated in Tables 7 & 8. Simply click on the link to each caption type to be brought to an anonymous external page that allows you to view the predicted captions alongside their target images.

- Im2txt Results

- Neuraltalk2 Results

- Seq2Seq Results

- Reference (Original) Captions

Results from Qualitative Model Evaluation (RQ4)

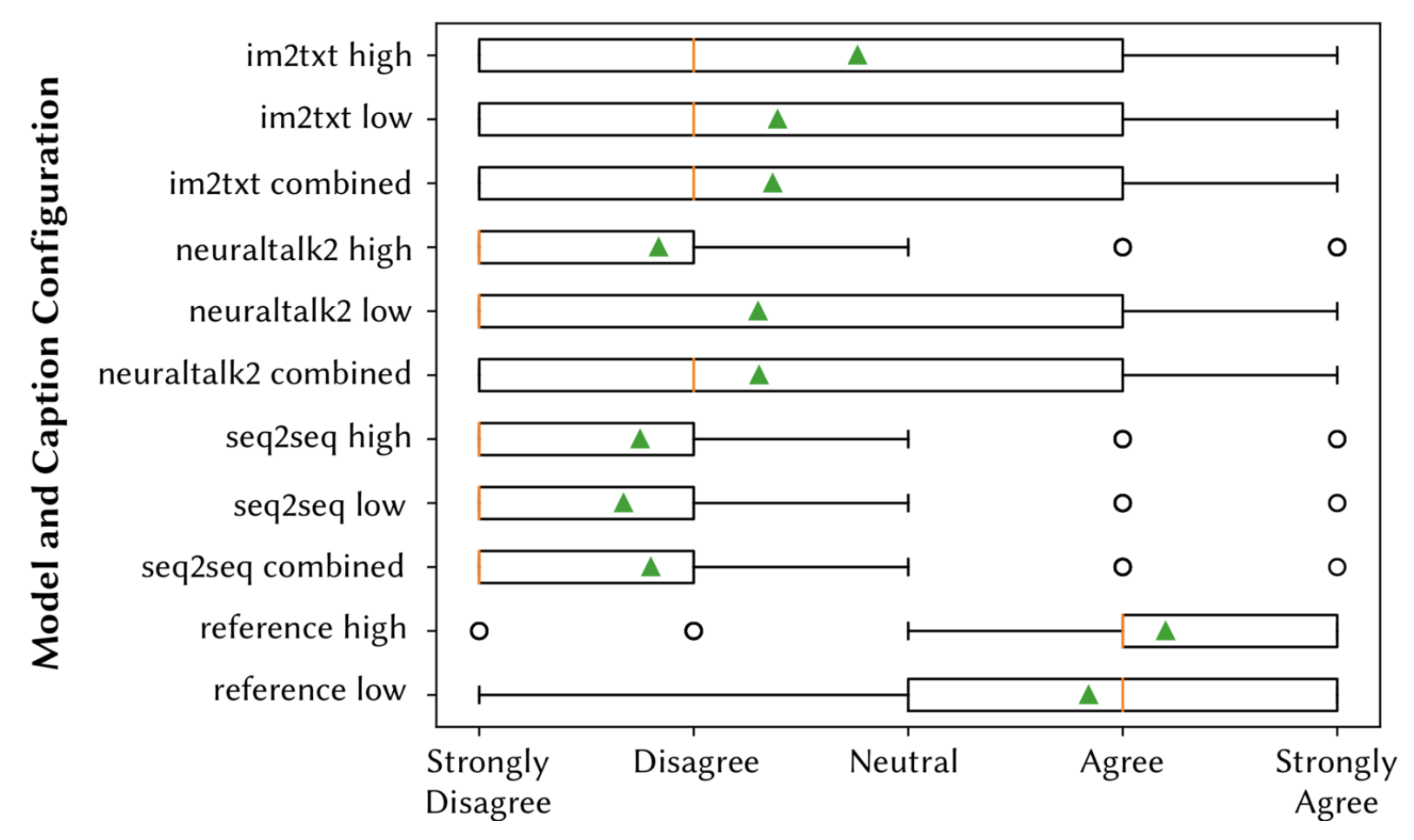

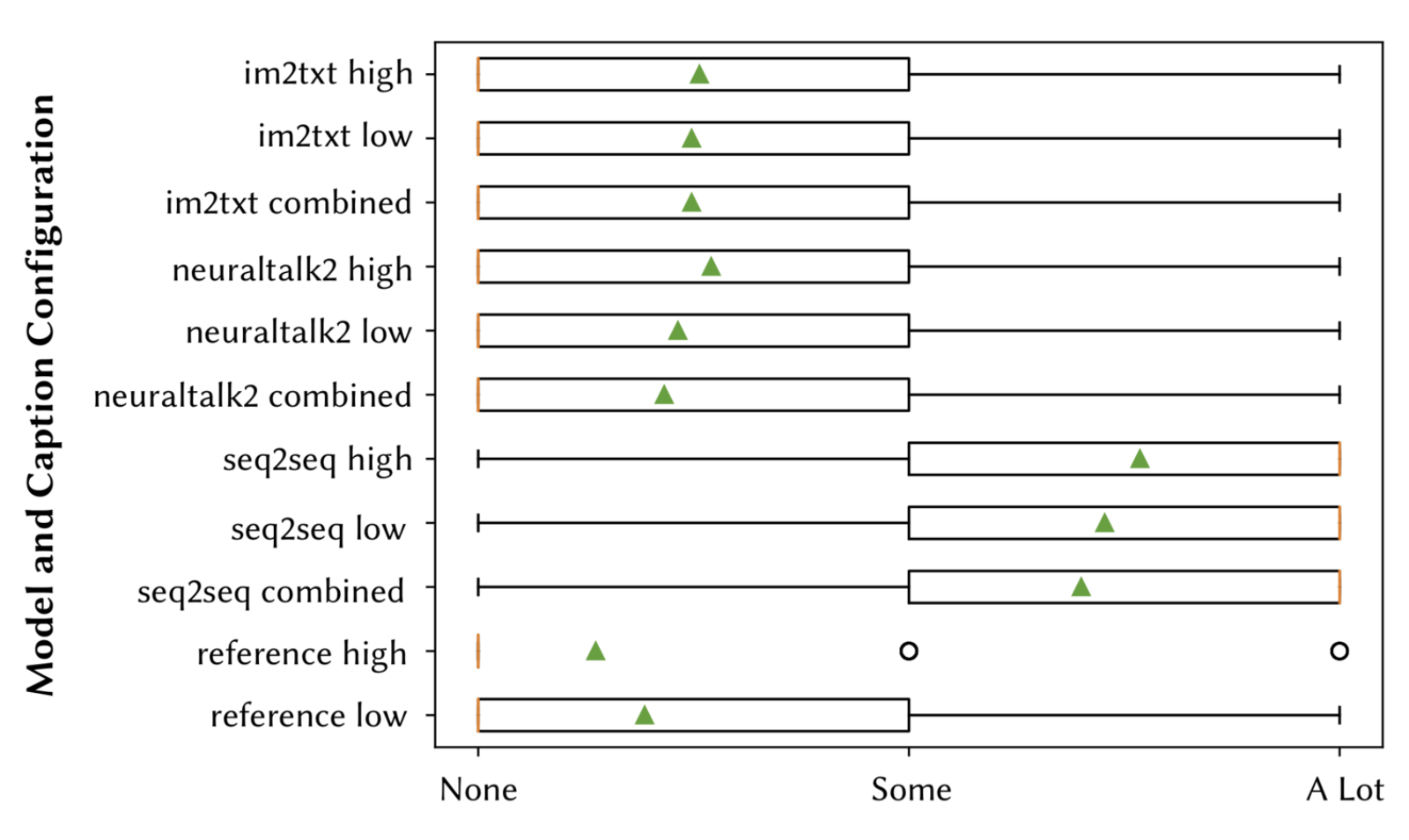

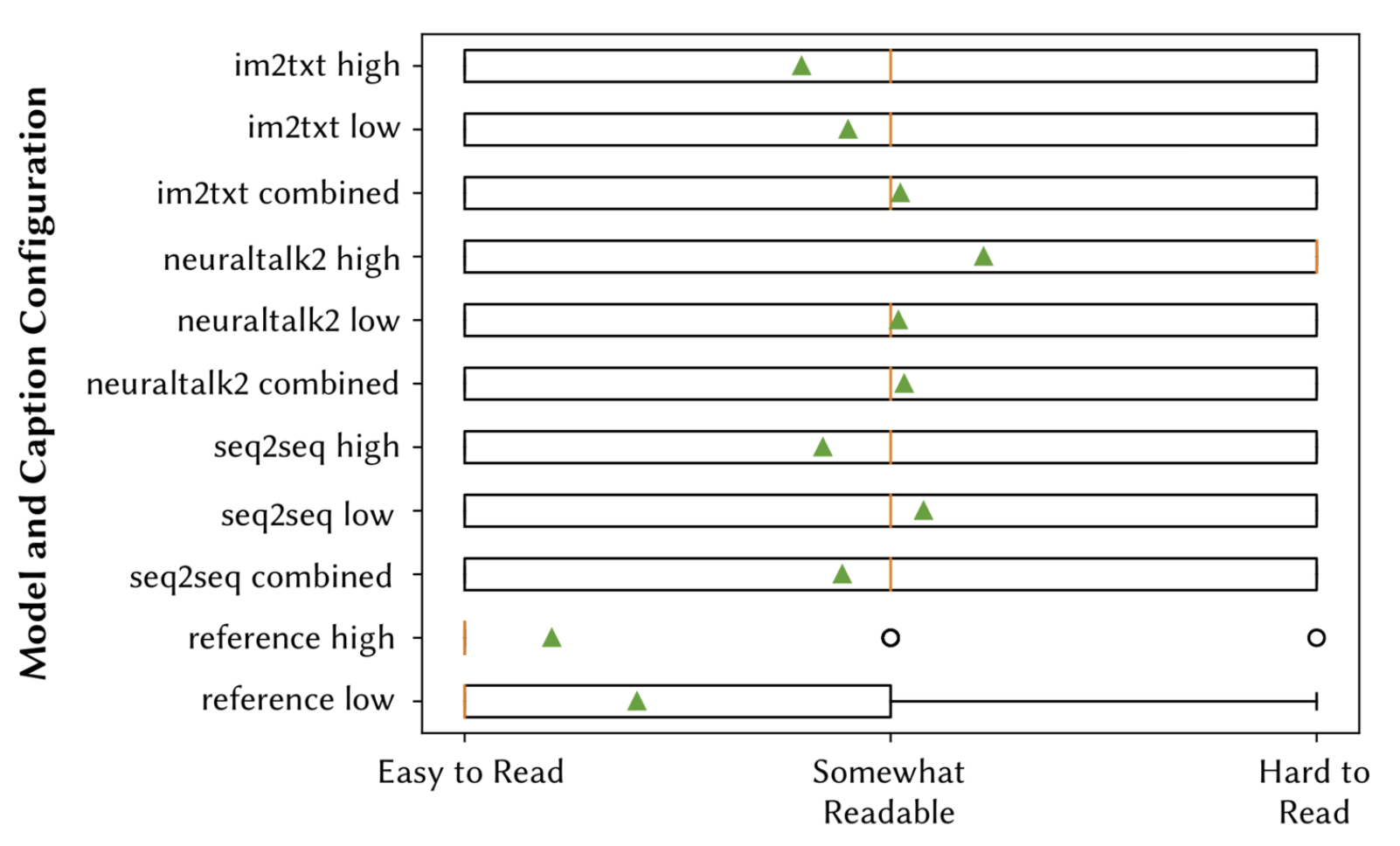

To qualitatively evaluate our studied model's generated captions, we performed a large-scale study involving 220 participants recruited from MTurk. We randomly sampled 220 screens from the Clarity test set, predicted high, low, and combined captions for them using the optimal configurations of im2txt, NeuralTalk2, and seq2seq according to the composite BLEU score for each model and caption level combination. We created a HIT wherein each participant viewed 11 screenshots paired with captions. Two of the 11 captions were reference high and low to serve as a control, while the other 9 captions came from the model predictions. Screens and caption pairs were arranged into HITs such that 1) no single HIT had two of the same screenshot, 2) each of the 11 types of captions (2 reference, 9 model) were included only once per HIT. The order of these captions was randomized per HIT to prevent bias in introduced by identical caption ordering between HITs. By this arrangement, each screen-caption pair was evaluated by 11 participants. After viewing these screenshot-caption pairs, participants were asked to answer several evaluation questions (EQs), denoted in Table 9, which were adapted from prior work that assessed the quality of automatically generated code summaries. Similar to the Clarity dataset collection, each participant's response was thoroughly vetted by at least one author, and were discarded if the free-response answers were found to be incomplete or inadequate. Responses were collected until 220 HITs were completed by unique respondents.

| QID | Question Text | Response Type |

|---|---|---|

| EQ1 | This description accurately describes the functionality of this screenshot. | Likert Scale |

| EQ2 | Considering the content of the description, do you think that the description has no/some/a lot of unnecessary information? | Three options |

| EQ3 | Considering the content of the description, do you think that the description is easy/moderate/difficult to understand? | Three options |

| EQ4 | What aspects of the description are accurate? | Free response |

| EQ5 | What aspects of the description are not accurate? | Free response |

| EQ6 | How could this description be improved? | Free response |

The results of EQ1 are summarized in Fig. 5, EQ2 in Fig. 6, and EQ3 in Fig. 7. The responses to EQ4-6 varied by the type of caption, and are provided as a download below. Respondents consistently verified the accuracy of the reference captions, suggesting only minor improvements such as grammar and additional functionality omitted in the original captions (e.g. "Call the UI element a button, not an icon. Mention that it's in a pop up dialogue". For captions generated from the deep learning models, im2txt fared the best in terms of accuracy, followed by neuraltalk2 and seq2seq respectively. For im2txt and neuraltalk2, in many cases respondents verified that the caption was accurate (e.g. "The description accurately describes the screen, it is in fact a terms and conditions screen." and suggested minor improvements similarly to the reference captions (e,g, "It could add specifics about what the settings pertain to (i.e. security)"). However, with seq2seq, caption accuracy was much lower, and respondents suggested more drastic revisions of captions, often times writing entirely new captions for EQ6 (e.g. "It should say 'There are two buttons at the top of the screen. One allows you to sign in. The other allows you to create a new account'."). For all of the deep learning models, accuracy was highest for the combined and low models, which corresponds to the much larger datasets used to train them.